Nothing puts us in a moood like reading that traditional milk is “making a comeback.” Sales of dairy milk rose 2% in 2024, driven largely by a spike in sales of the raw stuff, while plant-based versions dipped almost 6%. This is a big ol’ bummer. Un-milks have, on average, about one-third the environmental impact of dairy, and trading moo juice for an alt can carve 8% out of the average American’s diet-related emissions.

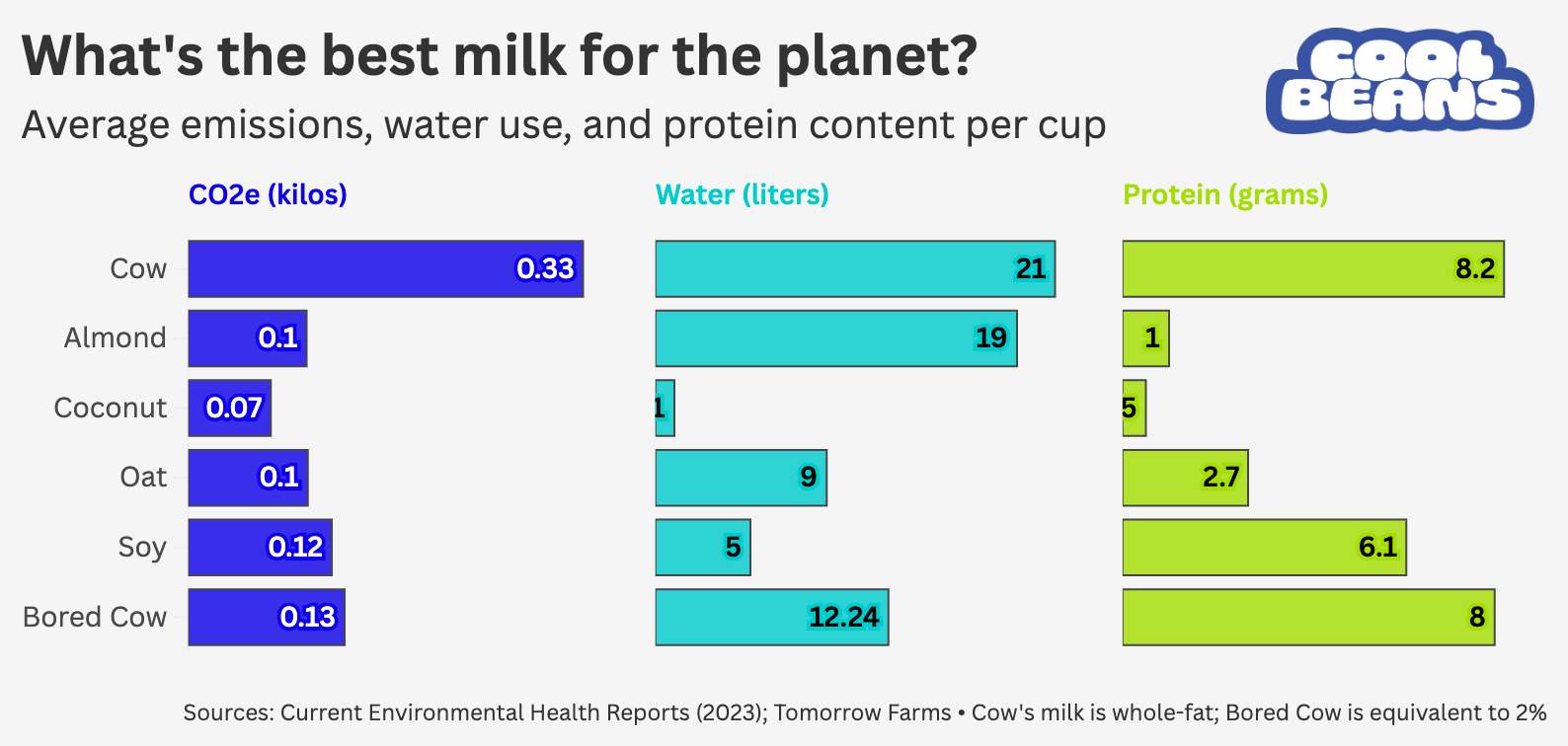

At the same time, critics often malign nondairy milks’ own impacts—particularly when it comes to how much water they use—so we decided to take a fresh look at the ever-growing field of alternatives and sort out which is best for the planet. We compared the emissions and thirstiness of the U.S.’s four most-popular not-milks (in order: almond, coconut, oat, soy) plus our favorite newcomer, a “bio-identical” swap from Bored Cow.

The environmental impact of making milk

Whether made from nuts like almond, fruits like coconut, legumes like pea and soy, or grains like oats and rice, plant-based milks all come about the same way. Producers soak nuts or grains in water, then blend and strain the mixture. (Coconut’s an exception: Processors press the milk from the flesh.) Some contain oils and stabilizers to improve consistency, plus vitamins and minerals to provide some of the nutritional values inherent in moo juice.

No matter the main ingredient, the whole process drinks up water, but the difference between products comes less in the blending and more from the plants themselves. Some trees are simply thirstier than others, and almonds are the worst offender. Estimates vary on just how much of the wet stuff it takes, so we looked primarily at a 2023 analysis published in Current Environmental Health Reports that averaged the findings from several studies. It found that almond milk needs 19 liters of H2O to make a cup—about double the thirst of oat milk, quadruple that of soy, and 20 times as much as coconut. Cow’s milk, however, is still the most draining: A cup has a water footprint of about 21 liters—or more than 5 gallons—most of which goes into growing the feed crops the livestock consume.

In terms of emissions, the differences between alt milks are scant, according to that same 2023 analysis. Almond’s planet-warming potential is on par with soy and oat, and only slightly above coconut, which is Americans’ No. 2 milk swap. Un-milks’ footprints come from a combination of factors, including potential deforestation to accommodate the crops and the energy it takes to grow, process, and package them. Regular milk’s planetary demerits, which are about three times higher, come from a combo of land use, growing feed, and the animals’ nasty habit of burping the potent greenhouse gas methane.

Bored Cow is the outlier in all this, because it’s made via a process called precision fermentation that makes it the same as actual milk from a biological POV—even though it requires no animals. How now, no cow? Rather than being expressed from a bovine, it’s “brewed” like beer: Instead of fermenting barley into Bud, specialized microorganisms ferment sugar into whey, a primary protein in milk. This process can be energy-intensive, but according to a life-cycle analysis commissioned by parent company Tomorrow Farms, making the product creates 44% fewer emissions than traditional 2% milk, and uses 67% less water.

So, what’s the best option?

Bottom line? Any of the nondairy alternatives are better than cow’s milk in terms of both emissions and thirst. If you want one with the lowest overall planet-warming potential, it’s coconut, then oat, then almond. Coconut milk, though, might not be the right choice for everyone: It’s higher in saturated fat than the other options (4 or 5 grams per cup), which is about the same amount as whole cow’s milk, and it’s a slouch in the protein department. Soy and Bored Cow come out on top there. More of a visual learner? No prob; we made a chart:

This article originally appeared in the

Cool Beans newsletter.

Read the whole story here.